Hello, who are you? What’s your story, coding glory? What are you good at, what do you like doing and what do you value? What are your hopes and dreams for the future? Tell me about your education and who you are. Which of your unique talents are you exploring and developing during your education? How are you striving to become a better version of you? Starting to answer these big questions, will help you develop better self-awareness. Exploring your future starts with knowing who you are now. 💭

Your future is bright, your future needs exploring, so let’s start exploring your future.

Improving Self-Awareness

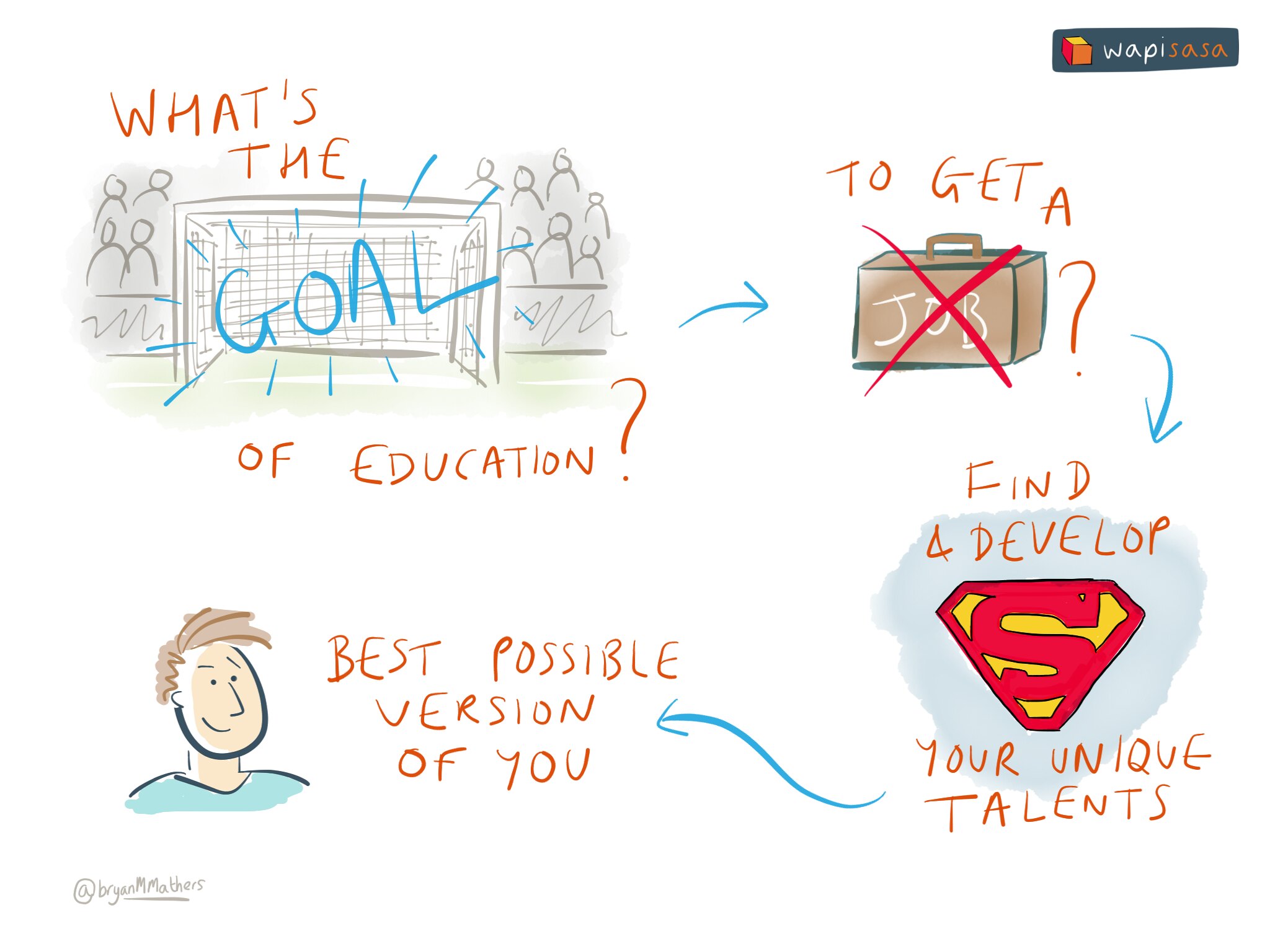

Exploring who you are now, will help you to understand who you might become in the future. That future you is the best possible a better version of you shown in 2.1. Since you started it as a small child, your education has been:

- about bettering yourself

- a key part of your identity

- inherently communal and social

At University only a fraction of your education will happen during formal lectures, labs, tutorials and seminars see figure 2.2

Your identity, who you are, is complex, dynamic and high-dimensional so you will need to experiment with several different techniques to improve your self-awareness. Here are seven techniques to get you started exploring who you are:

- 🔒 your protected characteristics, see section 2.2.1

- 📕 your story so far, see section 2.2.2

- 🙂 your head, heart and hands, see section 2.2.3

- 🤔 your reason for being (ikigai), see section 2.2.4

- 📊 your personality profile and skills, see section 2.2.5

- 💰 your privileges, or lack of them, see section 2.2.6

- ☠️ your deathbed thought experiment, see section 2.2.7

Your Protected Characteristics

Some of your identity includes characteristics that are protected. In the UK, the Equality Act of 2010 protects you from discrimination at work or in education, based on what are known as “protected characteristics”. (Servant 2025b). This means that:

- Your age should not determine how you are treated

- Your disabilities should not determine how you are treated

- Your gender should not determine how you are treated (Saini 2018; Damore 2017; Lewis 2017; Bates 2016)

- Your gender re-assignment should not determine how you are treated

- Your marriage or civil partnership should not determine how you are treated

- Your pregnancy and maternity should not determine how you are treated

- Your race (including colour, nationality, ethnic or national origin) should not determine how you are treated (Eddo-Lodge 2017; Saini 2019)

- Your religion or beliefs should not determine how you are treated

- Your sex should not determine how you are treated (Price 2019)

- Your sexual orientation should not determine how you are treated (B. Britton 2019)

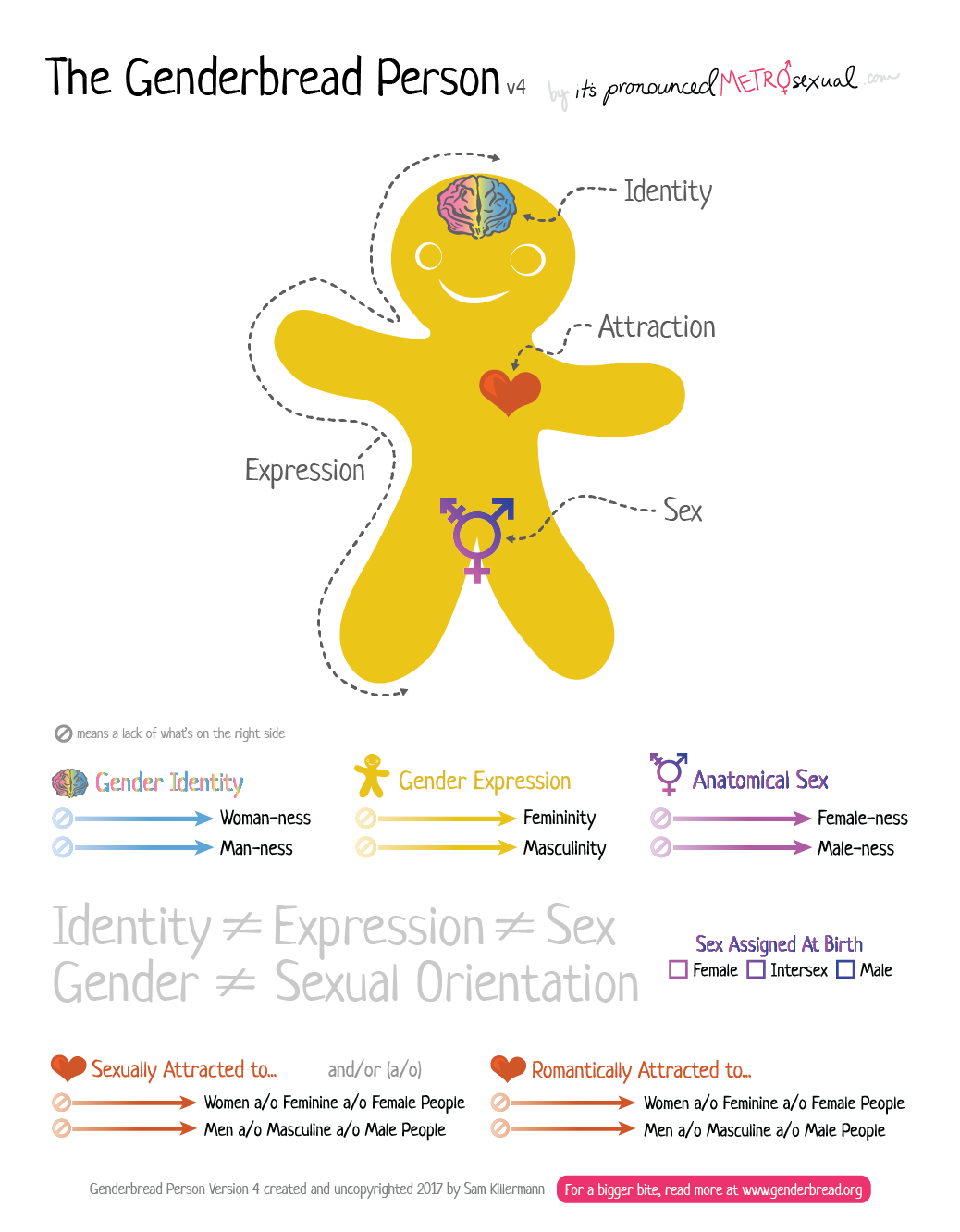

These are a special part of your identity because they are protected. This means they shouldn’t be a factor in apply for a job or a subject for discussion in a job interview. Let’s look at gender, sex and sexual orientation in more detail because they can be easily misunderstood. One way to understand gender better is to break it down into four characteristics:

-

Identity: your gender identity

-

Expression: your gender expression

-

Sex: your biological sex

-

Attraction: your sexual and romantic orientation

These protected characteristics are often conflated, because people tend to confuse gender, sex and sexual orientation. They are not the same thing as shown in equation (2.1)

\[\begin{equation}

Identity ≠ Expression ≠ Sex ≠ Attraction

\tag{2.1}

\end{equation}\]

Lets have a look at each of those in turn:

-

Identity 🧠 is who you know yourself to be in your own head. Gender identity is based on how much you align (or don’t align) with the options for gender based on your psychological sense of self. This includes, but is not limited to:

-

Expression 🎨 is how you demonstrate your gender based on gender roles through the ways that you act, dress, behave and interact. These are not exclusive categories, you might choose to express yourself in all three ways including:

-

Sex ⚧️ is often conflated with gender. Sometimes called anatomical sex or physical sex, your biological sex is objectively measurable using features such as your genitalia, chromosomes (your sex-determination system

XX, XY etc), hormones, body hair, ovaries and testes. Your biological sex includes, but is not limited to:

-

Attraction ❤️ is who you are physically, spiritually and emotionally attracted to. Like biological sex, sexual orientation is often conflated with gender but isn’t always a component of gender. We categorise the attraction we experience in gendered ways. Your sexual orientation includes, but is not limited to:

These characteristics are summarised in the genderbread person shown in figure 2.3

Gender is probably more complicated than you realised, but the framework above will help you understand it better or help you explain the subtleties to someone else by breaking a complicated concept into bite-sized, digestible pieces.

What’s your story, coding glory?

The protected characteristics described above are the part of your story you’ll be most aware of. But there’s much more to your story than these characteristics. We’re hardwired to love storytelling because it helps us understand the world around us, see figure 2.4. We use stories to organise and communicate, so knowing your story is a crucial part of knowing who you are and articulating that to other people, including potential employers. Your story sets you free! (Box and Mocine-McQueen 2019)

So, what’s your story, coding glory? (Gallagher 1995)

Understanding who you are and developing better self-awareness are important for leading a healthy and happy life, and likely to be an important factor in your future success. One way to develop better self-awareness is to think about the finer details of your story. (Box and Mocine-McQueen 2019)

- How did you get here?

- What has inspired you?

- Where are you going next?

- Who is the authentic you? (Ware 2011)

- What are your hopes and dreams?

By starting to answer these (admittedly BIG!) questions you will gain a better understanding of who you are. This includes your strengths, weaknesses, motivation and values. (Bolles 2019) Your story is complex but you need to know it so you can distil the details into much shorter stories on your job applications described in section 8.7. Crucial parts of your story are:

-

Characters: Who are the key people who have influenced your story so far?

-

Settings: Where and when have your stories taken place?

-

Conflict and change: Education means bettering yourself which inevitably involves change so:

-

How have your experiences changed you?

-

What did you learn from these experiences?

-

Emotions: how did you feel at the time? Fearful, happy, excited, surprised, empowered? Looking back, how do you feel about these stories now? Have your feelings changed and if so, why?

Write these stories down. By reflecting on them and articulating them, you will improve your self awareness. Ultimately, some of these stories can eventually be distilled down into content on your CV (with emotions edited out!), see section 8.7.8.

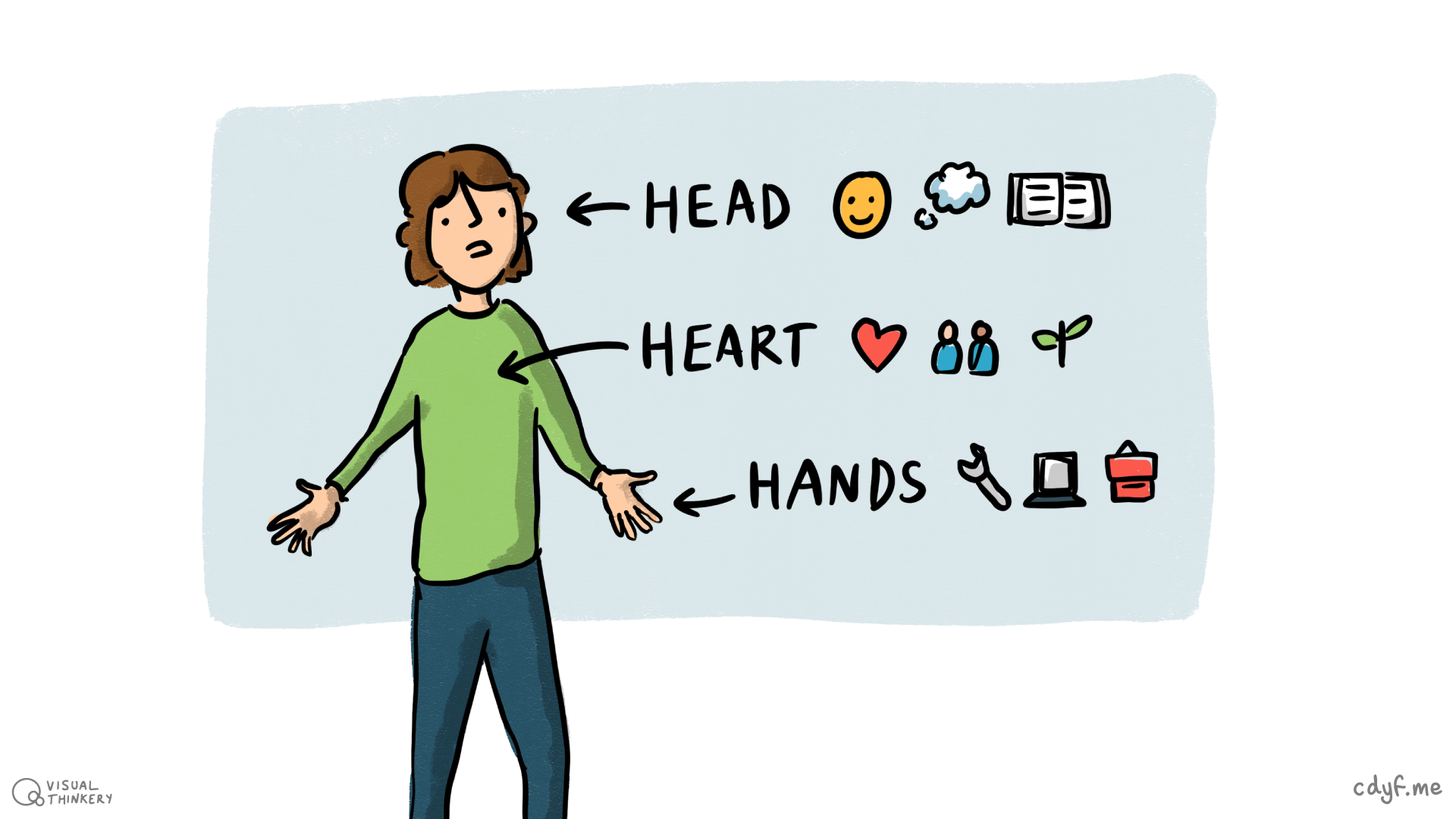

Head, Heart, Hands

Another technique for building your self-awareness is to reflect on your knowledge, values and skills. In Waldorf education and Montessori education this is characterised as “head, heart and hands” outlined below and in figure 2.5. (Easton 1997)

-

Head: What do you know?

-

Heart: What do you value, what motivates you?

-

Hands: What can you do? What have you done so far? What will you do with your skills in the future? Your actions define your impact, see chapter 10

Again, answering these questions will help you improve your self-knowledge and how you articulate that to potential employers.

Ikigai: Reason for Being

Many of the learning outcomes described above are non-trivial. You may have good self-awareness and be able to describe aspects of who you are in a matter of minutes. Other personality traits make take longer to uncover. You can develop better self-awareness by describing four attributes shown in Figure 2.6, together these are known as your ikigai (生き甲斐) or “reason for being”.

- what do you love doing?

- what are you good at?

- what does the world need?

- what can you be paid for?

You’ll be lucky if you can find activities at the intersection of all four sets (ikigai) shown in figure 2.6. In practice, you may realistically only be able to achieve one, two (the Passion, Mission, Profession and Vocation) or three intersections:

- 1️⃣: Happy and fulfilled but no wealth (not getting paid)

- 2️⃣: Excited and self approving but uncertain (not doing what you are are good at)

- 3️⃣: Feeling comfortable but empty (not doing what you love)

- 4️⃣: Feeling useless but also satisfied (not doing what the world needs)

It’s a valuable exercise to think about what is in each set for you. Take a sheet of paper, draw the four overlapping rings shown in Figure 2.6, and spend a few minutes adding your activities in each ring.

- What are your values?

- What motivates you?

- Are there things you like doing that you aren’t particularly good at?

- Why does that make them enjoyable?

Thinking about your ikigai will clarify your knowledge of yourself.

Skills & Personality Profiling

There are lots of tools you can use to build a profile of your skills and personality by answering some simple questions. These can help you improve your self-awareness, for example, the University of Manchester provides a skills audit shown in figure 2.8.

However you analyse them, auditing your skills will help you:

-

Assess your current skill levels

-

Learn more about your current profile and identify which skills you need to develop further

-

Explore and discover new ways to develop your skills in the skills pathways

-

Prepare for applications and write skills statements to use in future job and study applications

-

Reflect on your next step, track your activity and progress over time with the careers passport. Discuss your progress with your tutor, peers, academic staff and the careers service

Find out more at bit.ly/manchester-skills-audit.

Like the skills audit above, personality tests are designed to reveal your key characteristics, see figure 2.9. Besides helping you develop better self-awarness, they are used by some employers during job interviews. Personality tests are often part of a wider set of aptitude and psychometric tests to test measure your ability at numerical reasoning, verbal reasoning, logical reasoning and

situational judgement.

If you haven’t done a personality test before, the 16 short questions at careerpilot.org.uk/information/buzz-quiz will give you a flavour of what to expect. Which animal are you? There are lots of tools for personality profiling which go into more depth by asking you a lot more than 16 questions. Some of these services are free such as:

Different personality tests try to measure various dimensions of your personality such as:

- your relationship to other people

- your emotional intelligence

- your organisational skills

- your openness to new experiences

- your resilience and mindset

Your University may also pay for subscription-based personality and skills profiling services, check with your careers service for details.

Privilege Audit

If you have privileges, it is important to recognise and acknowledge any advantages these have given you in life. They are a key part of your identity, who you are and your ego. If you don’t recognise your privileges then you don’t know yourself. Ask yourself honestly, what privileges do you have? For example, is it just your skills and knowledge that have got you into higher education, or have you been fortunate?

- Don’t have too high an opinion of yourself and your privileges, otherwise you’ll overlook your flaws and won’t improve

- Be wary of your ego,

- If you’re struggling to think of any privileges, see section 2.4.4 for some suggestions.

- Your Education, a key part of your identity and who you are, is a likely to be a key privilege. Education is not a protected characteristic described in section 2.2.1, see figure 2.10, although some people argue that it should be (Rajan, Hix, and Radford 2022)

Being mindful of any privileges that you have is not just a part of knowing yourself better. Being grateful for those privileges is beneficial for your mental health too, see the discussion of section 3.4.

Deathbed Thought Experiment

Imagine for a moment you are on your deathbed. Not at some point in the future, but right now. Your heart (see figure 2.11), which has served you well until now, starts behaving strangely. You start having palpitations, hearing your own heartbeat (Hütter and Hilpert 2003) and worry what’s going on with the muscle responsible for keeping you alive. Worst case scenario is, your time is up. This happened to me and its a useful thought experiment to force you to think about what matters in your life. (Hull 2021b)

One of the things you’ll probably want to do is reflect on your life and wonder:

- What did you achieve?

- Do you have any regrets, if so what are they?

- What would you change if you could carry on living?

This can be a useful technique for forcing you to think about who you are and what you value. If you find this activity difficult, see section 2.4.1 for some hints. The Romans called this Memento mori which roughly translates from latin as “remember that you are mortal” or “remember that you have to die” .

Co-founder of desana.io Michael Cockburn argues that you should “make decisions as if you were on your deathbed”. (Cockburn 2022) Remember that you have to die. Memento mori. Do you realise that everyone you know someday will die? Instead of saying all of your goodbyes, let them know you realise that life goes fast. It’s hard to make the good things last. (Coyne et al. 2002)

Signposts From Here on Identity

This chapter challenges you to reflect on who you are and what you’re good at. We’ve only scratched the surface, so if you want to dig deeper you’ll find the following resources useful:

- The Top Five Regrets of the Dying

- What Colour is Your Parachute?

- How Your Story Sets You Free

- A range of books about privilege

What Would Your Dying Regrets Be?

One of The Top Five Regrets of the Dying (Ware 2011) is that people wish they’d had the courage to live a life true to themselves, and not a life that others expected of them. Figuring out exactly who your authentic self is can be challenging. Bronnie Ware’s book might help, it has some very moving, personal and insightful true stories of the regrets that people have that will illuminate your own values. The top five regrets, outlined in the book are:

- I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me

- I wish I hadn’t worked so hard

- I wish I’d had the courage to express my feelings

- I wish I had stayed in touch with my friends

- I wish that I had let myself be happier

You need to be courageous to live a regret-free life but the alternative is to die full of regret, see Bronnie’s video in figure 2.12.

Colouring Your Parachute

Since first being published in 1972, over ten million copies of What Colour is Your Parachute? have been sold. It has been translated into 20 languages and is used in 26 countries. What is good about Parachute is that it has some useful self-inventory exercises that go beyond the introductory ones in this guidebook, particularly in the context of your future career. While the style and examples can be U.S. centric, it’s a classic self-help book that looks at a broad variety of issues around job hunting. The author, Richard Nelson Bolles was a Harvard educated chemical engineer and explains how to work out what you’ll be doing in five years time in the video in figure 2.13. He looks at techniques for working our your direction including random luck, intuition and improving self-awareness, using similar techniques to those described in this chapter.

What’s Your Story?

A useful technique for developing self-awareness is to think about what your story is. Heather Box and Julian Mocine-McQueen’s book How Your Story Sets You Free (Box and Mocine-McQueen 2019) takes a storytelling approach to help you gain a better picture of who you are and what you value. What’s good about this book is its short, less than 100 pages and contains practical exercises which extend those in this chapter.

Check Your Privileges

Reflecting on your identity should lead you to check any privileges you might have. Being grateful for any privileges you may have is also beneficial for your mental health which we talk about in chapter 3 so:

If you think you got to where you are purely because of your talents, think again: there’s good evidence to show that luck plays a much bigger role than many of us would like to imagine. (Pluchino, Biondo, and Rapisarda 2018) Luck is as much a part of your identity as your talents.

There is a lot more to your identity than your race, class, gender and sexual orientation, see your protected characteristics in section 2.2.1.

Summarising Your Future

Too long, didn’t read (TL;DR)? Here’s a summary:

Your future is bright, your future needs exploring. Exploring your future will help you design you future. Designing your future will help you to start coding your future.

Know thyself was one of three maxims, or codes of conduct, proposed for coding your future and inscribed on the Temple of Apollo in Delphi, in ancient Greece, shown in figure 2.14. It’s still an important code thousands of years later. To explore your future, you must first know thyself. If you don’t know who you are know, it will be harder to expore who you might become in the future.

This chapter has looked at exploring yourself and who you are. Being self aware, understanding your strengths and weaknesses is key to getting what you need from your future. Questions about your identity are non-trivial, hopefully this chapter has improved your self-awareness and helped you answer some of the questions about what motivates you and what you want out of life. You will need to keep exploring your future because some aspects of your identity are bound to change over time.

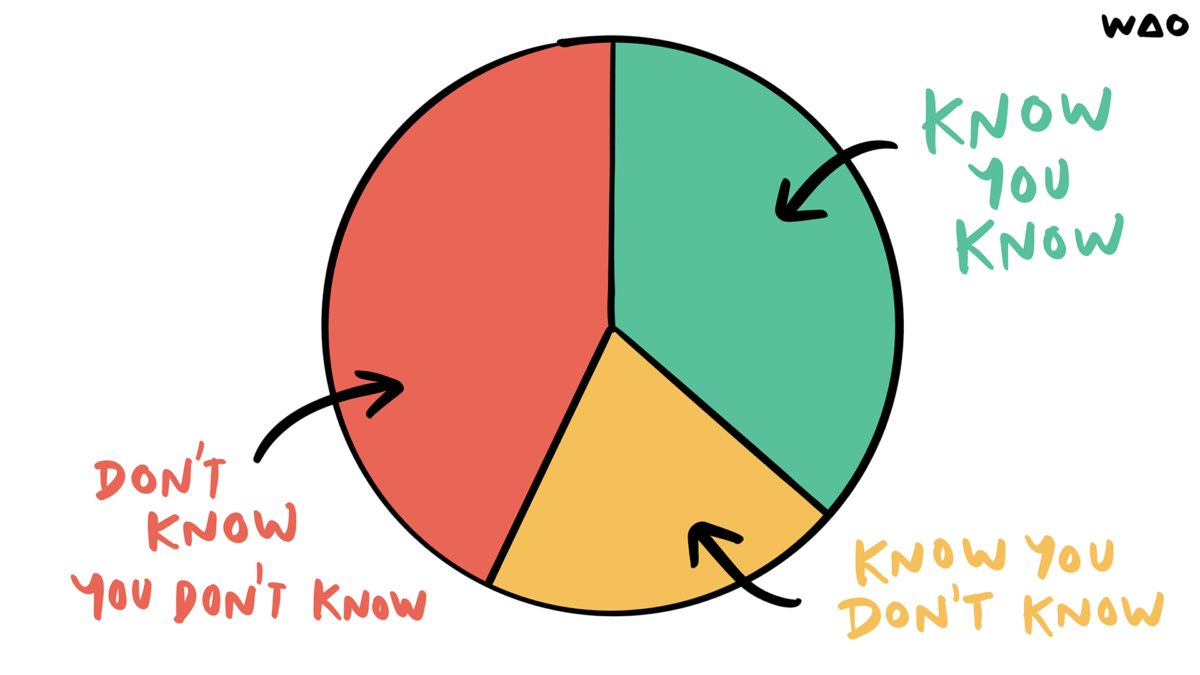

What do you know and what don’t you know about yourself, see figure 2.15? These fundamental design questions you’ll need to address when you starting building your future. This chapter has looked at some simple techniques for exploring your unknown unknowns.

Now that you’ve improved your self-awareness, in the next part we’ll investigate techniques for looking after your self in chapter 3: Nurturing your Future.